This year’s International Gamesweek Berlin established Virtual Reality as one of the main topics for the professional gaming platforms as well as for the consumer and education gaming activities.

Quo VRadis Berlin?

The game developer conference QUO VADIS dedicated a whole presentation streamline to VR topics, avoiding last year’s parallel sessions by means of audio headset channelling. Whereas last year’s conference was driven by excitement and curiosity about the upcoming VR wave, this year’s conference was marked by caution, precarious expectation and unconfident hesitation. This could partly be explained by the delay in PC headset distribution by Oculus and Vive and their thin starting line-up of contents for an emergent consumer market. But even the strong starting position of Sony’s PlayStation VR with the prospect of a couple of million headsets on the market by this Xmas season could not reassure the participants enough to preserve last year’s VR excitement.

Scary Moves: a panel on the business and design of VR as of today

The local industry seems to feel a certain discomfort with VR’s actual starting conditions and is looking for safety guidelines and orientation marks. Technical presentations focused on standard procedures like gaze interaction (Unity) or established gaming models like racing games (Unreal). Production presentations tried to bridge between conventional game development and VR porting options. Audio and interaction experts were looking to role models in other media areas or robotics. Scientific presentations turned the head to the past, offering well-structured talks on historical VR developments at the wake of today’s VR consumer market. Panels on ‘VR as of today’ detected ‘a remarkable silence’ in terms of current VR sensitivities. And all you could experience with VR on the show floor in real were three installations – only one of them market-ready, another one from an under-financed start-up and a serious game prototype from a school…

VR is a cliffhanger

Crytek’s ‘The Climb’ embodied this year’s conference dilemma and game industry’s struggling with new realities: by means of a conventional gamepad control of your bare virtual hands, you climb up a conventional game trail on a mountain rock in one of those beautiful landscapes the engine is famous for. The handling combines consumer conventions with headset surround vision by replacing physical experience with button pressing and tying the player’s gaze to the flat screen of the naked rock. The experience provides great VR views whenever you manage passage of the trail, but the climbing itself sticks to conventional gaming habits – one foot in the sky of VR, the other one in the gaming past. Crytek hangs in there between two worlds, demonstrating at the same time how to overcome the gap and how the industry’s limitations prevent from stepping out for it. Whereas my personal experience resulted in pain in the neck, the guy before me in line climbed up the game trail like a mountain ape: there definitely is an audience out there that can already be addressed with half-baked VR proposals. Even more irritating was the ambience of caution and insecurity at the show!

Hanging in there on the show floor with Crytek

Sony’s prospective outlook with PSVR could not really help for reviving the spirits: the Unity presenter was surprised how few participants work with a Move controller; rather shy feedback for Toxic Games‘ impressive portfolio of VR ready-mades for the PlayStation platform; only weak resonance at the expert’s panels on mentioning Sony’s next big step. What you could hear instead on the stage, at the show and in private talks was the mantra of “not enough headsets out there, yet”. This well organized VR channel was more interested in staring into the gap than in actually overcoming it. If you were searching for a pathway to the other side, you definitely had to look elsewhere.

Alternative Realms

The conference tried to fill the gap with offers from science, education and robotics. The VR presentation provoking the most vivid response from the audience was actually a historical review of VR development, making clear that there already is a lot of VR experience out there since a few decades – and that today’s operating frameworks provide more impediments than potentials for a fundamental VR recreation as they simply had not been made for this purpose. For once, the reaction in the audience showed some passion and spice, but I am not sure how many participants were actually coming from the game industry – this could well have been a moment for outsiders at this conference…

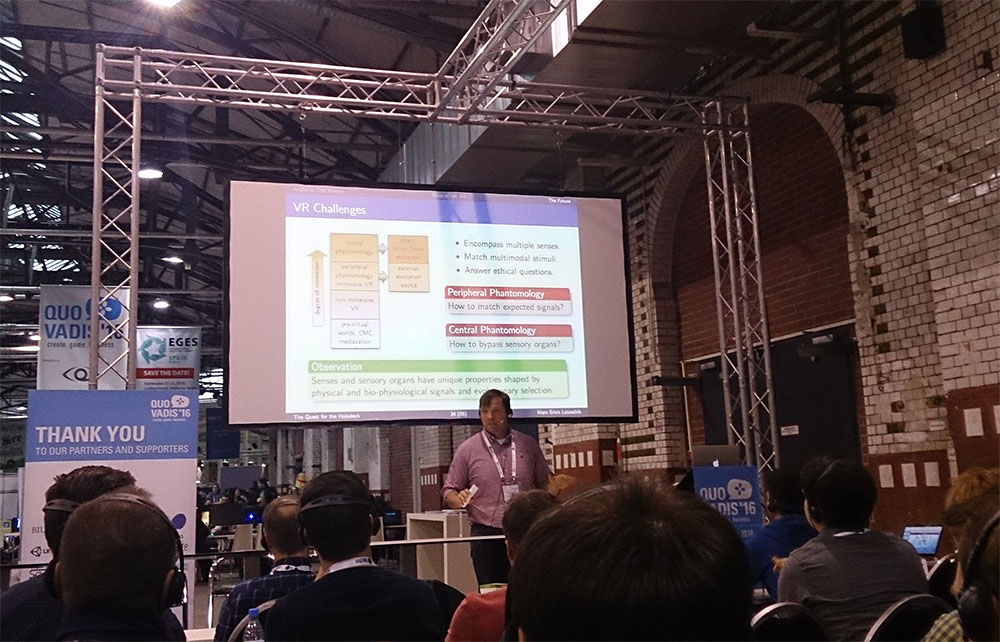

Uni Würzburg: history lecture on Lem’s ‘Phantomology’ as VR’s origin

Another example how to overcome the gap between gaming habits and VR challenges was shown by Stormborn Studios from Italy: they presented a prototype game for the Vive where the player is put into the role of a wizard, using the Vive controllers at the same time for motion gestures in first-person view and for conventional 3rd person movements through the magic realm. Both founders originally are not coming from the game industry which could be a strong hint to the future of VR games.

- Game Industry’s actual state of VR

- set into motion

- by magic ‘Runes’

- motion control

- surround vision

- world interaction

A Maze and the absence of ‘presence’

Berlin Gamesweek’s highly animated alternative video game show A MAZE also had more to offer for VR perspectives than the developer conference. About half of the game exhibition was related to VR installations: you could ‘Keep Talking And Nobody Explodes‘ or play ‘SelfieTennis‘ with a Vive; you could make ‘Lucid Trips‘, pass along electoral campaign stages in a surreal American landscape, train yourself in tricky headset gazing puzzles or simply perform as a ghost in ‘The Marchland‘.

In contrast to the commercial platform at Quo Vadis, the indie platform showed more VR experiences than talks about VR. Obviously, the current experimental stage of VR plays them into hands where the commercial companies feel handcuffed instead of grasping a market at hand.

But the gap between artistic experiment and commercial product is actually narrowing in comparison to last year’s enthusiastic departure into VR exploration. This year’s collection of high-quality experiences is already more established and more elaborated than last year’s experiments – and it is less surprising as well. Most of the VR works have already been shown elsewhere and come to Berlin with their own history. And they reflect the current switch in cutting edge production from distribution troubled Oculus Rift to installation-ready HTC Vive systems.

- SelfieTennis in VR

- Lucid Trips

- GearVR

- A Mazing Panel

Lucid Trips is a very poetic light-weighted experience in a surreal paper-made universe where the player rows her celestial virtual body in form of head and shoulders through an artful space world, collecting diamonds in a sky while enjoying the floating experience. ‘SelfieTennis‘ unfolds a cartoon world for comical solo gameplay, mimicking a Nintendo world at the same time as paving the way for commercial toy games in VR. ‘Keep Talking And Nobody Explodes‘ says it all in the title and combines boardgames instructions with virtual headset blindness in a very funny and communicative way. ‘The Marchland‘ is a stimulating and deeply atmospheric stage design within tiny interiors of a little house where the player can penetrate the walled micro-space by becoming a ghost.

- The Marchland

- starting as a visitor

- looking around

- becoming a ghost

- finding out

- being a camera

Although all these installations and game proposals playfully represent the excellent possibilities for independent enterprises in VR at the moment, you can already feel how technological and commercial standardization will soon mark their conditions: the political landscape simulation in a DK2 headset already seems passed in aesthetics and interaction design before the elections take place by the end of this year; the GearVR puzzle gazer resembles Valve’s commercial Portal Demo from last year’s trade shows; ‘The Marchland’ tries to turn a current VR misconception into an artistic concept, but a ‘camera ghost’ is more a ‘presence’ problem than a VR feature. Some works already fall behind industrial experiments, some only illustrate technological conditions instead of overcoming them – and conceptual originality will be the only way to make an artistic difference to upcoming commercial standards in VR.

VR Twilight Zone

Whereas the commercial game industry waits and sees, and the independent game industry plays and frees, both platforms of this year’s Gamesweek seem to be hanging in the same intermediate state – between well established or well-mimicked gaming standards and yet incomplete conceptual pathways.

Nothing could reflect this situation better than an installation at the Berliner Computerspielemuseum, where the Gamefest was located: an old VR Cybercafé setup from last century’s final decade was reanimated for today’s kids by means of an Oculus Rift headset – the same ghost in the same machine, as if Virtual Reality bites in its own tail.

1990’s VR revival at the Gamefest

Despite the general outlook of prospective VR sales rates by the end of this year and despite the local subculture’s tradition of fearless conception, the International Gamesweek Berlin is cautiously looking for a position at the long tail of VR before the head of this market even shows up.